Devonport Gallery 2024 Solo Commission 27th April - 10th of June

Ten seconds of forever: Notes on Atmospheres

By Andrew Harper

Here is a soft bubble that is not soft.

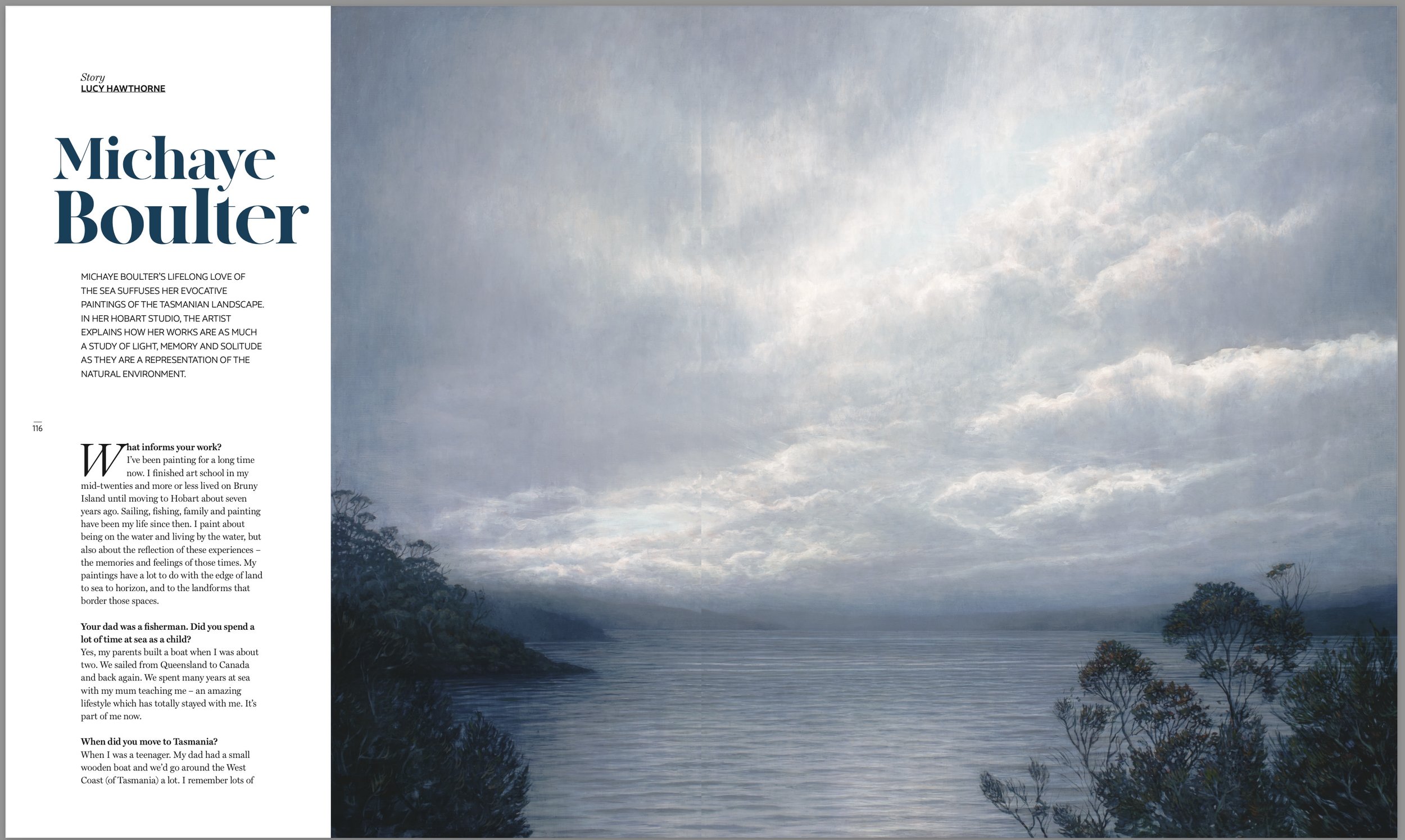

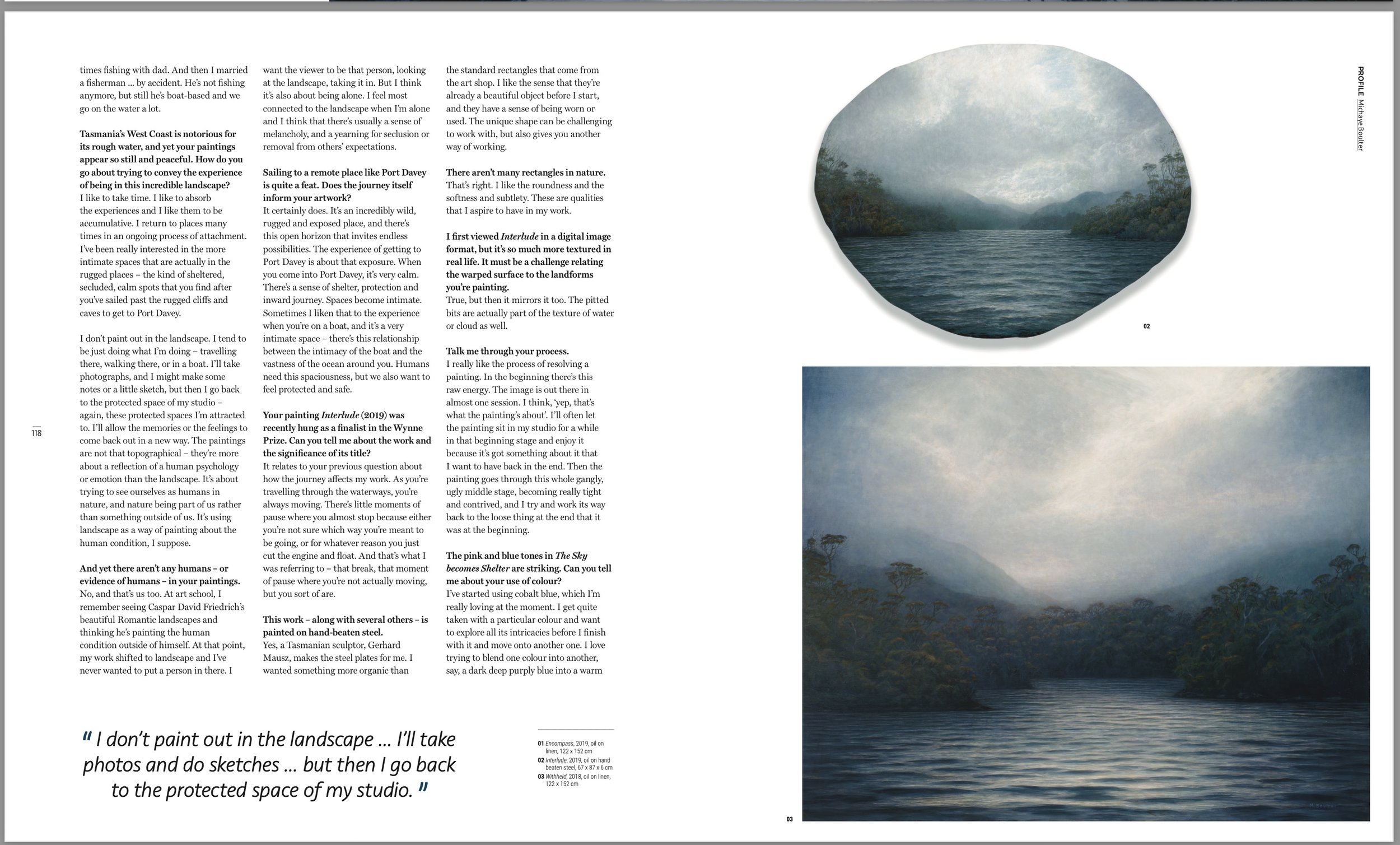

A painting evoking contradictions: a vision set onto metal, its irregular edges suggesting flotation. Dark yet luminous. A fragment of shoreline, where the calm sea meets proto-calligraphic, sharp coastal flora. It invokes a fleeting memory, a cut out of something that is lost. Like one of those memories that are a bright shard, a sliver of a whole event. We saw this place like this. We were doing something. We were playing. Hear the gentle, persistent lap of the water? It must have been here, then, but there is no other information: only this soft bubble. Somewhere in the back of our minds it echoes, existing in a place outside of everything.

When thinking around the work that composes the collection of paintings that is together called Atmospheres, strange things swam into my mind: metaphors or analogies to approach describing the art. This is somewhat giving the game away, but I think that the workings of any mind around the subjectivity of art are endless. That is: everyone will see what they need to see. We all bring ourselves to art.

In this instance, to assist me in my very own subjective interaction with the work of this complex and enigmatic artist, I turned to a single shark. The Greenland Shark. A specific beast, almost five metres in length and born somewhere between 1504 and 1744. This shark passed through a tumultuous period of global history – probably without noticing the passage of human-chronological-time, intent only on feeding and reproduction, oblivious. Of course, the shark experiences time, as all living things do, but it has no need to measure it with clocks, calendars, alarms or historical periodisation. It exists in time, but also next to it, untouched by time’s human-organisation. Not knowing it is the oldest living vertebrate on the planet[1]. That knowledge is useful to us, but does not matter to the Greenland Shark, old, slow, and drifting. It does not know we call it a Greenland shark, and in truth, the shark has many names, its habitat stretching wide across the North Atlantic, named and lifted into myth by multiple differing human cultures that populate that vast, cold region.

I see the oldest Greenland Shark as a parallel to Michaye’s art. Her paintings reach into notions of time and space but are not defined by them. Michaye’s art and what it shows exists on its own terms, not as oblivious as the shark, but perhaps as cryptic, as mythically distant.

Michaye’s paintings are strange. They have their own rules and logic.

Forget what they show for a moment and look at their many edges, their formal structures. Look at the lines, the borders, the overlays, the overlaps, whatever you might understand them to be. Much of what Michaye is doing in her art is overlaying and overlapping the edges of one image of a certain place with another image of that same place (this is actually a guess on my part. The pearlescent, luminous sky shown in one floating rectangle that slices across the golden shard of sunlit cloud that sits in another shape, both which float atop another, and so on – that first placement might be from another part of the world entirely but lets us hedge our bets and suggest that all the visions, collaged together, come from roughly the same region of Lutruwita/Tasmania). These edges and borders and lines can be found anywhere within one of Michaye’s works; and do not look for order or symmetry; It’s not there and it’s not needed. The logic comes from within the artist.

The overlapping, layered quality of Michaye’s paintings is reminiscent of the techniques of collage, but also of divination: something emerges from the places where the edges meet. A new image is made by finding a way to place two images that do not match exactly together, and something fresh and wet and old and floating is made that is not simply a rendering, an image of a space; it’s another way to see, and it exists outside of what we might call narrative space.

Michaye works in an avowedly non-linear manner. Her imagery folds and creases boundaries, slices off edges and mixes views. She is not rendering a reproduction of an existing space: she is creating new images from images of an existing space, that may not exist in a concrete way anyway. There is no story; that is replaced representations that shift the moment depicted to a location outside of the experience of linear time. This something only the intent of art can do, no matter the medium (although Michaye has made paint work well here); art can vivisect time and re-arrange it, make it new, make it strange and wild. Michaye cuts and melds visions of time and place, removing linearity.

When we look at Atmospheres, we see temporal bubbles that exist outside of time as we experience it. Perhaps that’ s why I thought of the Greenland shark: it seems to exist next to time rather than in it. Michaye’s works depict interlocking and clashing moments that are certainly informed by memory but are not fragments of a story as much as they are portals into a new, created, vision of a space: it is as if Michaye has dug into the fabric of a location, pulled it asunder with her hands, tearing the very air open and stared into this alternate reality. She has found a still, no-place that exists next to wherever we are. It’s an idea of silence and light, and it doesn’t exist, yet is composed of images of somewhere that did, at least at a one time, which is now gone, and exists only as rendering of a memory of an image, seen by the artist, and filtered through her own complex, arcane processes that render linear understanding irrelevant.

There are hints of science fiction, of the fantastic in that analogy, but do recall the deep subjectivity of all art: when you see this work you see a space the artist knows, as well as the folds between that space; you see the mood-riven waters and the places where the sky blooms gold, where the water meets a forest, and that hushed, breathing space is filled with secrets that people can never know. There is a dank silence butting next to a glowing brisk brightness. We see the places, the meetings of island and forest and water and cloud. We see the segments of Michaye’s work overlapping and merging: trees, sun, clouds, the rich dense plant life, all of it: all rendered as a vision, images of images of images, layers of layering of a setting known and loved, seen through many moods and changes of season and time. It is yesterday and last week and five years ago, all at once, and it is also none of those moments. The images are moved sideways, swimming forever, doing what they need to do to simply be themselves, drifting outside the very furthest edge of forever.

[1] This shark is one we know of. It is very likely there are others just as old, and perhaps older.

Exhibition Catalogue Essay by Elli Walsh

Towards Light Arthouse Gallery Nov. 18 - Dec. 10, 2022

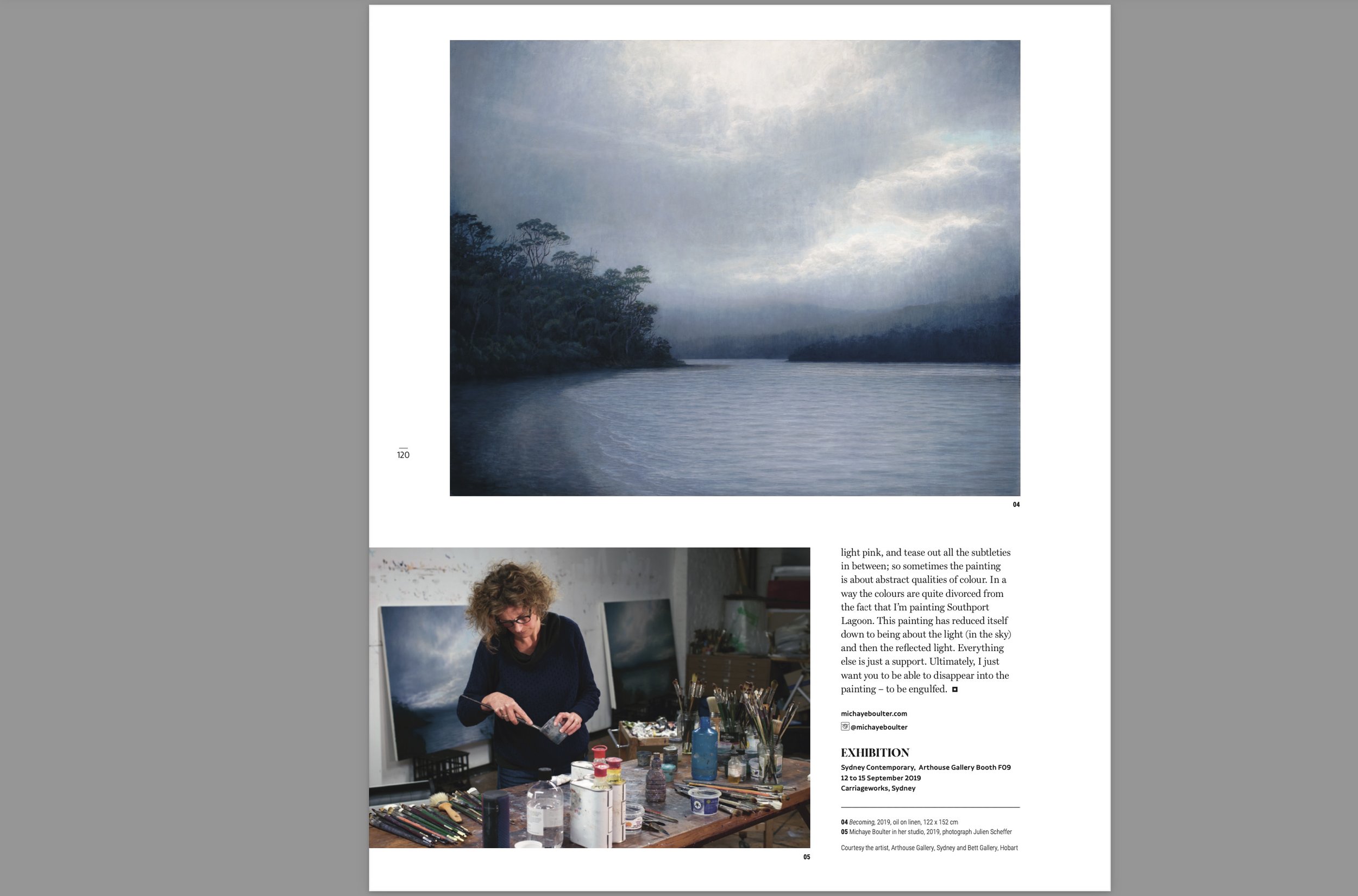

The deeply evocative paintings of Michaye Boulter reflect a lifetime spent on and around the ocean, exploring the ways we summon memories of place as markers of our ever-morphing identity. From her home on Bruny Island to Recherche Bay, the otherworldly landscapes of Southern Tasmania are conduits for Boulter to explore the representational and abstract qualities of atmosphere, with all its somatic and ontological energy.

Boulter’s latest series of paintings on linen, board and steel chronicle a metaphysical journey, a daydream, stretching across space and time to an imaginary destination – a place of reverie. The artist explains, “For me, reverie is the mind untethered at play. In the quiet solitude of the places I love, I am free to wander and wonder, what hidden colours and visions emerge? What memories, what ineffable realisations sustain me?” Certain Tasmanian landscapes, so fond and familiar, are her departure point to entering into a liminal state where the senses are sharpened and the world feels intensely evocative. This concept of ‘departure’ encapsulates the emotional valency of the works – as a feeling of being comforted by and embedded in place whilst harbouring a yearning to leave, a longing for the unknown.

The tiny details of Boulter’s natural surroundings are accented in this series – elongated grasses graceful in their sway, mesmeric rock bed mosaics, dense bush curtained in mystery, and ensembles of ancient trees on the borderline between land and sea. Orchestrated yet wild, these compositions radiate from within; an inexplicable glow that feels both fleeting and forever. “Nestling myself amid the smell of wet grass and earth, the lure of light is inescapable”, reflects Boulter. “In the fading day, bush colours intensify, the low light spills across the water and thickens over distant land. A world disappears. A portal opens to another shore, another time.”

Still waters and symphonic trees are silhouetted against ethereal skies in an eternal unfolding. As if by gravity, we are pulled towards the ubiquitous horizon, engulfed by the mesmerising emptiness in between. It is from within this void – free from spatial and temporal strictures – that we glimpse scintillating interplays of the finite self and the endless ocean, tethering us to the continuum of existence. Every now and then the trees whisper and the sea sighs, exhaling an eternal breath resounding truths too quiet to hear, too profound to penetrate. The emotional sincerity of Boulter’s subject shimmers against the virtuosity of her brushwork. ‘Towards Light’ sees the artist continue to hone her painting techniques developed over many years. Boulter works patiently and intuitively, applying countless layers of oil like luminous veils that both reveal and conceal the landscape, allowing the work and ideas to build slowly, symbiotically. The foreground bush is captured in veneers of thin paint, drawing out shades of sienna, light cadmium orange, warm reds and pinks, while pale grey skies are conjured via layers of ultramarine and sienna. The perspective, here, has altered with a synthesis of near and far.

Alongside paintings on linen and hand beaten steel (the latter an ongoing collaboration with Gerhard Mausz), ‘Towards Light’ presents smaller works on board for the very first time. Rendered with a greater range of colour, these experimental and experiential paintings are like fragments, portals, stages for ideas and imaginings freely executed. They are a gathering of transient moments, micro worlds at once becoming and dissolving. Harnessing the traditions of the miniature, these new works are personal and precious to Boulter. She tells us, “I recall the viewfinder I had as a child. Looking into its binocular shape was a slide show of another world. Looking inwards, ever deeper, was paradoxically intimate and expansive. It is a sensation I try to emulate in my work – that of the boundless stretch of the world as a metaphor for the mind.”

‘Towards Light’ is an invitation into Boulter’s intimate experiences of self and landscape, beckoning us to slow down, see, listen, reflect, and engage in our world’s quiet songs of enchantment.

Elli Walsh

Deputy Editor, Artist Profile

Conversation with Heather Rose for exhibition catalogue what stays within Bett Gallery 2021

Artist Profile Magazine 48 - Story by Lucy Hawthorne